ReSwift, a weird use case

ReSwift, a weird use case

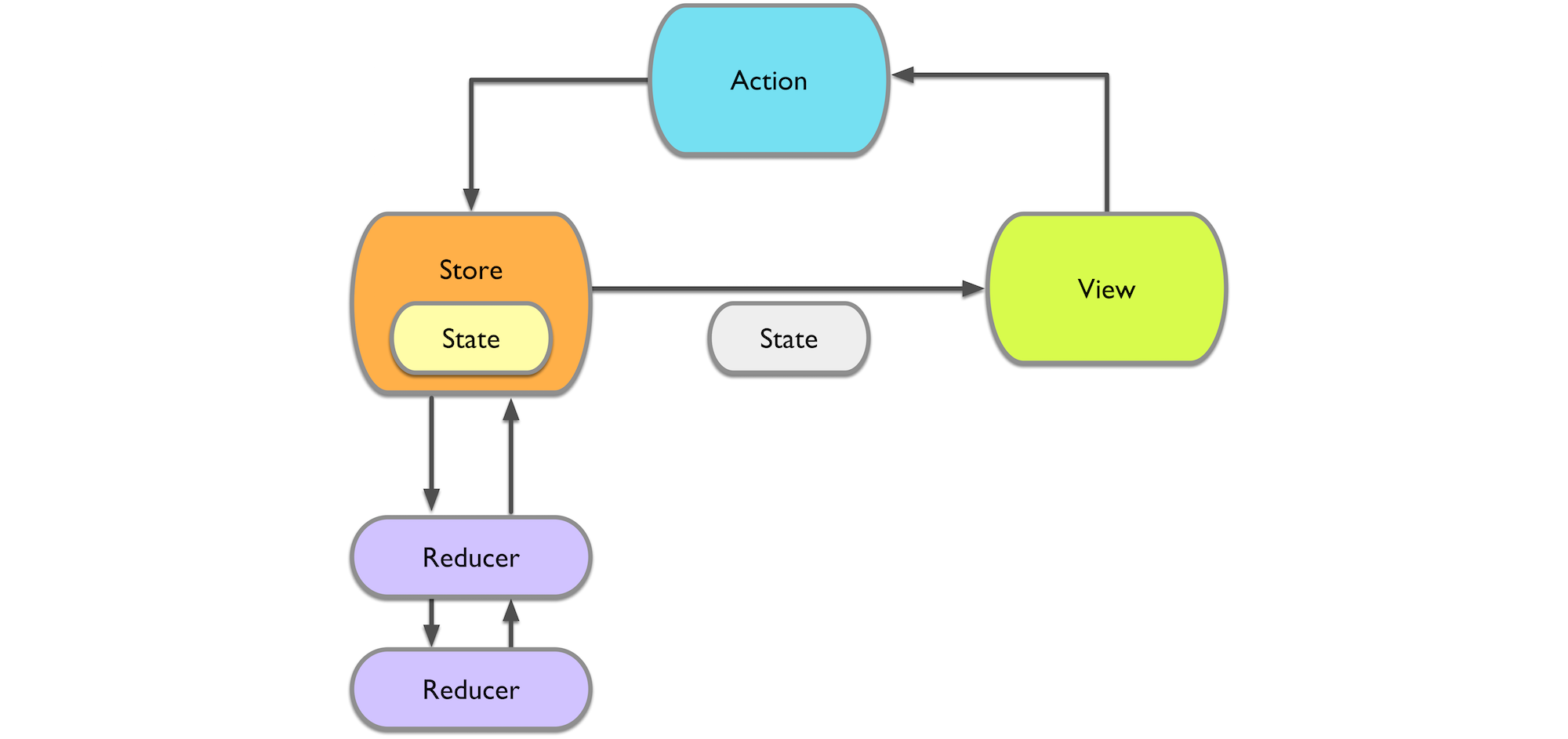

ReSwift is a library helping you construct unidirectional data flow architecture in your application. If you’ve already known Redux, think of ReSwift as a Swift implementation of it. I’ve tried ReSwift in my project, and I love it. It’s lean, easy to understand and easy to write. As always, however, practical use is far more than theory or the introduction at first glance. The more I use, the more problem I explore and need to deal with them. In this post, I’ll discuss my use case of ReSwift.

ReSwift in brief

Before discussing the use case, let’s give ReSwift a quick rewind. Here, I recall a few principles on which ReSwift relies (from its README):

- The Store stores your entire app state in the form of a single data structure. This state can only be modified by dispatching Actions to the store. Whenever the state in the store changes, the store will notify all observers.

- Actions are a declarative way of describing a state change. Actions don’t contain any code, they are consumed by the store and forwarded to reducers. Reducers will handle the actions by implementing a different state change for each action.

- Reducers provide pure functions, that based on the current action and the current app state, create a new app state.

The above is just high-level description about store, actions, and reducers. In practical use, you might want break one big app state down into many smaller states to work with easily. So are reducers, each reducer will take care of an appropriate state. Action is simply a structure to encapsulate information needed to change the state.

The use case, first introduction

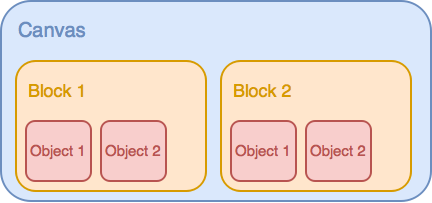

Now, let’s talk about the use case. To keep it short and simple, what I want is visualized below.

There’re 3 main components: canvas, block, and object. The relationship between them is described as: Only one canvas contains one or many blocks; Each block contains one or many objects. Based on this relationship, I can define the appropriate basic state for each.

struct CanvasState: StateType {

var blockStates: [BlockState]

}

struct BlockState: StateType {

var frame: CGRect

var objectStates: [ObjectState]

}

struct ObjectState: StateType {

var frame: CGRect

}

I have CanvasView, BlockView and ObjectView corresponding these components, and each will display its state.

class CanvasView: StoreSubscriber {

func newState(state: CanvasState) { }

}

class BlockView: StoreSubscriber {

func newState(state: BlockState) { }

}

class ObjectView: StoreSubscriber {

func newState(state: ObjectState) { }

}

So far, I have the skeleton for the project, how about functionalities? Basically, I want to have these ones:

- Display components based on their state.

- Remove block.

- Update object, it can be position, size, or other attributes.

- Remove object.

In fact, there are more than this, but for the sake of brevity and simplicity, that’s enough.

Display

In the hierarchy, canvas is the highest level component and manages immediate lower level component, block. Block manages objects in turn. Therefore, to display all components, canvas and block need to traverse their child states, and add them to the view hierarchy.

class CanvasView: StoreSubscriber {

func newState(state: CanvasState) {

for blockState in state.blockStates where /* `blockState` isn't yet added */ {

let blockView = BlockView()

addSubview(blockView)

}

}

}

class BlockView: StoreSubscriber {

func newState(state: BlockState) {

for objectState in state.objectStates where /* `objectState` isn't yet added */ {

let objectView = ObjectView()

addSubview(objectView)

}

}

}

class ObjectView: StoreSubscriber {

func newState(state: ObjectState) {

}

}

Since newState(state:) is called every time the state changes, and I don’t want to duplicate views if they’re already added, the where condition in the loop does the job. However, the detail implementation won’t be discussed in this post. The display part is straightforward, let’s move to functions.

Functions

Having the advantage of unidirectional flow from state to view, functions can be represented by actions in ReSwift. On the other hand, if I want to have a function, I need to do the following:

- Declare an appropriate action which packs information needed by the function. For example, moving a block requires the block index, so there’ll be

BlockActionRemoveaction.

struct BlockActionRemove: Action {

let index: Int

}

- Update the reducer to handle

BlockActionRemoveaction. - Then, whenever I want to remove a block at a particular index, a simple action dispatch call suffices.

store.dispatch(BlockActionRemove(index: index))

Display, revisit

I talked about display and functions, and so far so good, everything’s typical and goes well. However, when the number of objects increases, performance becomes an issue. Since every object subscribes to the store, even a small change in one object causes all get re-displayed. The performance, therefore, is the sum of the display costs of objects. One obvious solution for this is to re-display the only objects with changes, and this leads to diffing the state. There’re few diffing strategies I can consider.

- Object level: Still loop through all object states, but only call

newState(state:)with ones have been changed. This’s an out-of-box feature in ReSwift 4. - Block level: At this level, the loop is limited to only block states. Block only re-displays its changed objects based on the diff result. This’s equivalent to that subscribers now are just canvas and blocks.

- Canvas level: This’s the highest possible level. The principle is identical to block level.

In my use case, the number of objects is far larger than the number of blocks, and the number of blocks is reasonable small for traversing all without overhead. Clearly, diffing at block level is the most suitable choice because it offers the balance between having more control on state delegation and utilizing ReSwift’s. I need to make some updates to accommodate this. Firstly, let’s define diff result.

enum Diff {

case initial

case add(indices: [Int])

case change(indices: [Int])

case remove(indices: [Int])

}

This diff result needs to be in block state so that when the block view displays its state, it will use the result to display objects.

class BlockView: StoreSubscriber {

var diffResult: Diff?

func newState(state: BlockState) {

switch diffResult {

case .initial: // Add all objects.

case .add(let indices): // Add objects with index in `indices`.

case .change(let indices): // Update objects with index in `indices`.

case .remove(let indices): // Remove objects with index in `indices`.

}

}

}

diffResult will be nil if there’s no change for objects in the block. Note that objects don’t subscribe to the store anymore, but they still have the same interface as a subscriber.

class ObjectView {

func newState(state: ObjectState) {

}

}

The weird thing

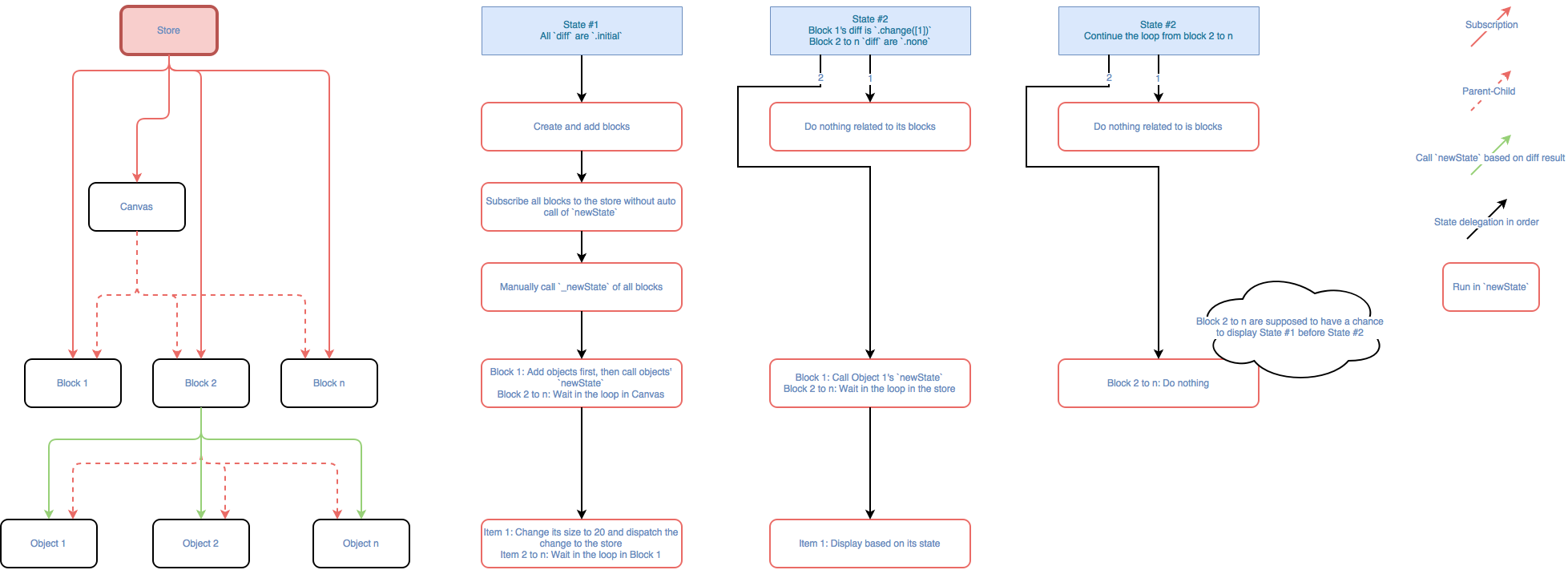

As for functions, normally, we dispatch an action when the state delegation is settled which means every subscriber gets its new state and update corresponding to the state. What if we disrupt the state delegation, i.e., dispatch an action while the delegation’s happening? Here’s when the weird thing comes. The following diagram will describe best the problem.

Whenever there’s an object dispatching an action during state delegation, i.e., dispatch in newState(state), blocks after the block containing the object don’t update their objects. There’re factors causing this:

- The diffing, it helps improve performance, but also increase the complexity when working with ReSwift. However, even if objects are displayed not based on diff result, there’s still another problem, and I’ll talk about it in the next point.

- ReSwift works in a synchronous manner and has one single store. If we make store change in

newState(state)which equals to calling anothernewState(state)inside anewState(state), eventually we’ll end up with recursivenewState(state)calls or nested state delegation, and that’s another problem I just mentioned earlier. Additionally, because of one single store, regardless iteration of the state delegation,newState(state)always gets the latest state. That’s the reason why block 2 to n don’t have a chance to displayState #1andState #2in the diagram.

In essence, I have two problems. The first one is that objects don’t get updated under discussed circumstance. The second one is nested state delegation which doesn’t affect the visual result but harms the performance.

Solution

Now I know the causes, finding solutions would be easier. Eliminating the diffing may solve the first problem, but the second problem’s still there, worse it’ll double slow down performance. Taking snapshot of the store so that each iteration of the state delegation has the correct state to display seems promising. Though it’ll break original idea, also philosophy of unidirectional data flow from ReSwift, Redux or even their ancestor, Flux, so let’s move on. I also won’t break synchronous ReSwift, and try to make it asynchronous since the problem isn’t about asynchronous so far. Ideally, what I want is whenever an action dispatched from newState(state), it should be queued in and performed after the state delegation finishes. By that way, I can keep ReSwift works synchronous and make it happy with the diffing. Surprisingly, it’s not a big deal to achieve that.

class ObjectView {

func newState(state: ObjectState) {

// If needed to dispatch an action.

DispatchQueue.main.async {

store.dispatch(Action())

}

}

}

The main is a serial queue and ReSwift already works on it, so it’s the perfect way to synchronize the state delegation and action dispatch in newState(state).

Alternatives

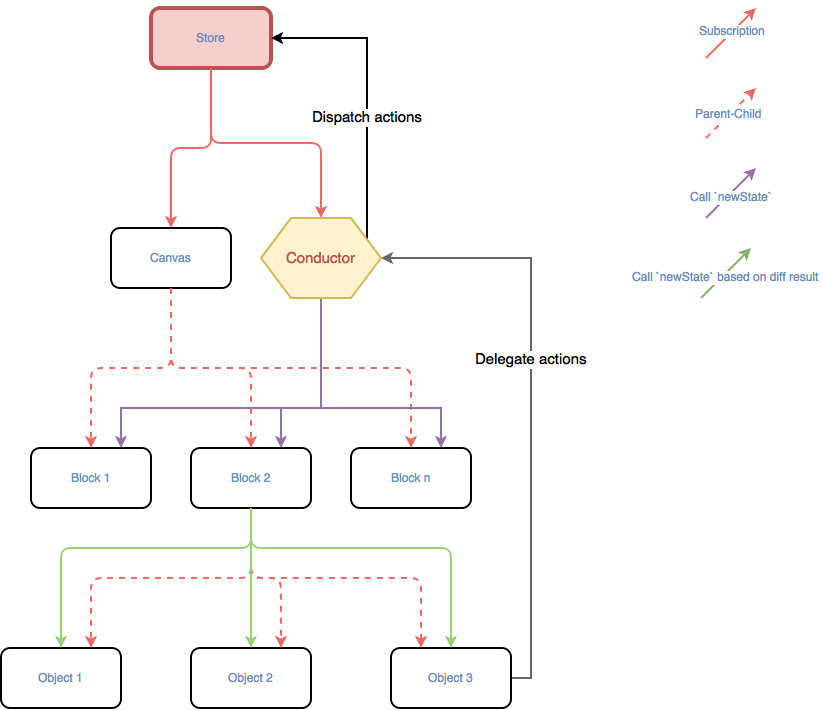

Apart from the above solution, we can use a conductor to orchestrate action dispatch in newState(state). Instead of dispatching directly to the store from object, we delegate the action to the conductor. The conductor, then, will batch actions and dispatch once to the store after all blocks get their new state.

Another option is action creator. Action creator can create either synchronous or asynchronous action, and the latter one is what we need. However, this solution comes with a caveat. Let’s examine two scenarios.

class ObjectView: StoreSubscriber {

func newState(state: ObjectState) {

if size == .zero {

store.dispatch {_, _, callback in

callback { _, _ in

return Action()

}

}

}

}

}

class ObjectView: StoreSubscriber {

func newState(state: ObjectState) {

if size == .zero {

store.dispatch {_, _, callback in

self.viewModel.fetch { _ in

callback { _, _ in

return Action()

}

}

}

}

}

}

The action in the former scenario is created outright if a certain condition is met, i.e., the action is created synchronously. In this case, to use action creator we need to know when the state delegation is done to call callback to create the action, that creates extra work. Maybe, we can call callback in DispatchQueue.main, it turns to the above simpler solution though. In contrast, the latter one fits perfectly to use action creator.

When to go from here?

The discussion on a weird use case of ReSwift is to demonstrate a practical application of ReSwift and overcome obstacles in real world usage. Though mentioned asynchronous action dispatch in newState(state), it’s just the surface of an iceberg. In the consideration of the whole project, there’re many corners to have a look on, improve and deal with, e.g., the diff algorithm, flattening the state, state changes in between of asynchronous action dispatches, etc. Moreover, this post is written limited to abilities and features of ReSwift 3, ReSwift 4 is already out there for few months though. Finally, unidirectional data flow in iOS opens new opportunities and perspectives, and in conjunction with reactive programming, architectures, they’ll create a thriving playground for writing better code.